The supply to cities has been academically discussed as a challenge of urban development for decades. Despite all the city logistics concepts, a solution has not yet been found. Meanwhile, the pressure to act continues to increase. Causes and solutions of modern urban logistics are discussed over two Logonomics issues. What are the potential solutions?1

The supply to cities has been academically discussed as a challenge of urban development for decades. Despite all the city logistics concepts, a solution has not yet been found. Meanwhile, the pressure to act continues to increase. Causes and solutions of modern urban logistics are discussed over two Logonomics issues. What are the potential solutions?

The trend of urbanisation remains unbroken – Solutions for urban logistics are being sought more and more urgently

Ever more people around the world are living in metropolises. Currently, about 50% of the world’s population is living in an urban area. By 2050, the United Nations predicts that figure to be almost 70%. Increasing urbanisation also applies to Germany. At the end of 2019, around 40%2 of the population in Germany lived in a densely populated area, i.e. in areas with a population density of more than 500 inhabitants/km2. This is also one reason why population growth has extended to the suburbs.

All these people need to be taken care of. In the past decade, people have increasingly turned to alternative shopping options on the internet. The Covid-19 pandemic has significantly exacerbated this trend in the face of closed city centres. With the increase in private, commuter and delivery traffic and the rapid development in e-commerce, the volume of traffic is increasing more and more.

At the same time, the demands on city centres are increasing. The idea of sustainability and quality of life in metropolises are increasingly coming to the fore. The consequences for cities include increasing traffic and emission restrictions.

And it is precisely at this point that the dilemma reveals itself. In order for cities to be able to continue to guarantee attractive living spaces as well as needs-based supply in the future, a functioning urban logistics system that brings both developments into harmony is becoming increasingly urgent. However, there is still no concept that completely solves the dilemma. Traditional or area-wide concepts fall short here, as the ‘European city’3 has grown organically and is thus very heterogeneously structured. A mix of different approaches and concepts based on a scalable basic structure is more promising.

The problems, and approaches to solving them, are discussed in more detail below.

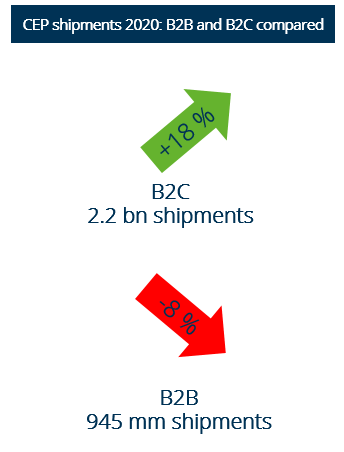

There is no denying that the ever-growing share of e-commerce has also led to an enormous increase in courier, express and parcel (CEP) shipments. Triggered by the corona pandemic, a new record result was achieved in 2020 with over 4 billion shipments. The breakdown into shipments to companies and consumers shows a very contrasting picture due to the pandemic. Due to the lockdown measures, online trade (B2C) has experienced unprecedented hype, while deliveries to businesses (B2B) have declined. For the time after the pandemic, it can be assumed that this increased online share will be maintained in the B2C sector – people have built the new convenience into their everyday lives too much. In the B2B segment, a significant increase in parcel volumes is expected due to the economic upturn. Taken together, therefore, the pressure on cities is intensifying.

Against the background of rising parcel volumes, it is obvious to link the increasing congestion of city centres with the simultaneous rise in internet trade. Provided this trend can be stopped, everything will be fine. The solution is simple – traffic needs to be taken out of the city. But is the chain of argumentation coherent? Looking at Hamburg as an example city reveals an interesting contradiction that shows that reality is once again more complex.

Of course, the transporting of parcels generates traffic. And the perception is that more parcels are synonymous with more traffic. Subjectively perceived, road users are constantly stuck in a traffic jam caused by a delivery vehicle. The problem is: the volume of traffic in Hamburg has been falling for years. Statement and numbers do not match.

A look at the traffic volume and the traffic count points via heat map reveals that the traffic load is distributed in a dispersed pattern over almost the entire urban area. If CEP vehicles were the main cause of the traffic volume, then there should at least be indicators that give clearer signals for the most important transport routes. The question is therefore: what else contributes significantly to paralysing the flow of traffic?

Hamburg was one of Germany’s congestion capitals in 2020, second only to Berlin, with a congestion level of 29%6. However, a request6 shows that the development of traffic in Hamburg is declining overall. This development particularly affects the areas ‘City’, ‘Core City’ and ‘City Streets’ and applies to motor vehicle traffic as well as heavy goods vehicles. An increase in traffic can only be observed for the areas ‘Motorways’ and ‘state borders’7. How can this discrepancy be explained?

For a passive and neutral observer of urban traffic, the lively diversity of urban traffic participants resembles an urban traffic laboratory and thus a cross section of our modern society with all its characteristics.

Multiple road users paralyse the city centres:

In addition, public transport buses or new forms such as the driving service MOIA as well as commuter and private transport such as tourists with their cars are very present on the streets of the metropolises. Double-parking is interpreted as almost conforming to the rules, but it makes the flow of traffic even more difficult.

Figure 5: Example of digital supply concepts: Delivery by Flaschenpost. source https://www.businessinsider.de/gruenderszene/allgemein/flaschenpost-sammelt-50-millionen-ein/

Figure 6: Examples of sustainable transport concepts: Self-driving bus of the Hochbahn and a vehicle of the driving service MOIA, photo: Christian Hinkelmann, Source https://www.nahverkehrhamburg.de/moia-stellt-betrieb-in-hamburg-voruebergehend-ein-hvv-haelt-angebot-aufrecht-189342/

Many of the road users mentioned above are characterised by having a high stop density. The following traffic has to slow down again and again and traffic jams build up.

The transport infrastructure is characterised by growth on the one hand and a maintenance backlog on the other. The result is a large number of roadworks, which are often poorly coordinated between the city centre and the roads/motorways in the surrounding area of Lower Saxony, and in some cases considerably impede the flow of traffic.

Looking at the multitude of road users and external circumstances, it becomes clear that picking out one road user obscures the bigger picture. Delivery traffic is only one of many factors and not the cause of urban gridlock.

The topic of sustainability plays a central role for metropolises. Due to the measures to reduce emissions (noise and air pollutants), other road users are increasingly coming to the fore. In concrete terms, this means that, for example, the footpaths and cycle paths are extended and thus road space for cars/trucks is taken away. In addition, areas in the city will be closed or severely restricted to motor traffic. In Hamburg, for instance, a central place like the Jungfernstieg became largely car-free8. This is absolutely understandable and to be supported against the background of quality of life, but for the flow of traffic it is a further hindrance.

How can an imminent traffic collapse in metropolises be prevented and the quality of life improved at the same time? Certainly not by ignoring or forgetting delivery traffic in urban development concepts9. Certainly, it is understandable for political reasons and also goes down well with voters if neighbourhoods aim all urban development measures at creating living space and quality of life. However, when ordered goods, sometimes even critically needed ones, do not arrive on time, resentment grows. In the pandemic, logistics was recognised as ‘systemically relevant’. Will there be much left of it when lockdown and incidence values are forgotten again? It is to be hoped that there will be greater awareness of the fact that urban logistics is also a (system-relevant) stakeholder in the city.

The bottom line is that there are basically two facets that need to be optimised for functioning urban logistics. These are new concepts of goods handling that are still primarily carried out outside the city gates. Especially for last-mile distribution, the logistics areas must be organised close to the customers. Almost synonymous is the transport itself. How can a transformation into the future succeed here?

Read on in the next issue to find out which concepts support demand-oriented and sustainable supply in urban areas and what potential solutions are offered by cargo bikes and micro-depots.

Figure 7: Cargo bike instead of delivery van – Hochbahn opens micro-depot in the city with logistics partners. Source: https://hamburg-news.hamburg/innovation-wissenschaft/hochbahn-eroeffnet-mit-logistikpartnern-mikrodepot-der-city.

1. Classification of urban logistics / distinction from city logistics: The term city logistics refers to the solution approaches in the primarily academic discussion, which goes back to the 1980s, but was able to solve the problem of urban supply with the exception of pilot projects. Aspects and developments of e-commerce were hardly considered. Urban logistics, on the other hand, takes these current challenges into account and encompasses a broader spectrum of stakeholders, including the real estate industry. It also includes large-scale property types (e.g. e-fulfilment centres) that are generally located in the surrounding areas of metropolitan areas. Urban logistics must therefore be seen in an overall context and does not stop at the city limits. We therefore refer to urban logistics as a frame of reference within this article.

2. Source: German Federal Statistical Office.

3. Note: The European city is characterised by a very high level of diversity in a small space. A mixing of work and residential functions in buildings is present as well as an increasing land value from the periphery to the centre.

4. Source: BIEK, M-R-U GmbH.

* Note: The percentage shows by how much the average journey time is increased compared to a journey with normal traffic flow.

** Note: Average daily traffic on working days.

6. Note: This is how much the average journey time increases compared to a journey with normal traffic flow.

7. Source: ‘Written Small Question’ by MPs Rosa Domm and Gerrit Fuß of 22 October 2020 to the Hamburg Senate.

8. Source: https://www.buergerschaft-hh.de/parldok/dokument/73036/entwicklung_des_verkehrs_in_hamburg.pdf.

9. Source: https://www.hamburg.de/pressearchiv-fhh/14456328/2020-10-15-bvm-verkehrsfuehrung-jungfernstieg/.

10. Source: https://www.openpetition.de/petition/online/bewohnerparken-im-quartier-mitte-altona.

We use cookies on our site. Some of them are essential, while others help us to improve this website and to show you personalised advertising. You can either accept all or only essential cookies. To find out more, read our privacy policy and cookie policy. If you are under 16 and wish to give consent to optional services, you must ask your legal guardians for permission. We use cookies and other technologies on our website. Some of them are essential, while others help us to improve this website and your experience. Personal data may be processed (e.g. IP addresses), for example for personalized ads and content or ad and content measurement. You can find more information about the use of your data in our privacy policy. You can revoke or adjust your selection at any time under Settings.

If you are under 16 and wish to give consent to optional services, you must ask your legal guardians for permission. We use cookies and other technologies on our website. Some of them are essential, while others help us to improve this website and your experience. Personal data may be processed (e.g. IP addresses), for example for personalized ads and content or ad and content measurement. You can find more information about the use of your data in our privacy policy. This is an overview of all cookies used on this website. You can either accept all categories at once or make a selection of cookies.