Germany’s online retail sector experienced tremendous growth in 2020 and 2021, the years of the COVID-19 pandemic. While the annual growth had fluctuated between 9% and 12% during the run-up to the COVID-19 outbreak, it accelerated to 23% and 19%, respectively, during those two years. For the sake of comparison: The revenue growth in the retail sector as a whole equalled 6.2% and 1.6%, respectively, during the same period. In 2021, online sales in Germany climbed to a peak level of EUR 86.7 billion. Last year saw them level out in a mild consolidation – with sales registering a slight year-on-year dip (-2.5%) for the first time.

In 2022, e-commerce claimed a share of nearly 20% out of the retail sector’s total revenues, making it one of the most established markets in Europe. In fact, it is the highest level among the major EU countries and second only to the UK (26.5%). The online retail share in Spain and Italy, by contrast, is around 10%, a threshold that Germany already crossed in 2014. In fact, the share in Germany is expected to increase by roughly another 10% by 2028.

Figure: Trend in online sales (net) in Germany, 2000–2022

The brisk expansion of online retailers during the COVID-19 pandemic was matched by a significant increase in the demand for logistics facilities by this same group of occupants. While the demand generated by them started to flag noticeably in the second half of 2022, classic retailers picked up the slack. Having accounted for 19% in 2020 and for 20% in 2021, online retailers saw their share in the take-up total tumble to as low as 13% in 2022.

During the first nine months of the ongoing year, physical and online retailing together claimed a mere 19% of the total logistics take-up. This means the take-up decreased by around 70% over prior-year period. So, do the latest take-up figures point to a market saturation? And how is online retailing likely to develop in general going forward?

The consolidation of the online retail sector has continued this year. By the end of the first nine months, retail sales lagged 13.7% behind the prior-year figure. The drop is primarily attributable to the general development of the economy in combination with the inflation surge. Private households have reigned in their consumer spending because the increased inflation exposes them to a significantly higher cost burden. Meanwhile, the persistently high order frequency for online retailers indicates that the current trend in revenues is subject to economic effects above all, more so than to industry structure effects.

As far as the final quarter of the year goes, industry experts are unaware of any factor that would stimulate consumption growth. If the decline for the year as a whole were to match that of the first nine months, the year-end total would roughly match the level of 2020 – a year of enormous growth.

In other words, the development of online retailing is currently slowed by consumer reticence above all. But to some extent, the decline can also be blamed on a shift of consumer focus back to in-store shopping after the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. The argument is backed by the fact that total retail revenues during the first quarters declined by only 4.6% over prior year. So, what development impulses are at work within the industry and which trends are in evidence?

The textile sector is undergoing its next revolution at the moment. While online fashion retailing in Germany had been dominated primarily by H&M and Zara, two major European players, in years past, two Chinese groups, Shein and Temu, have been expanding their market shares lately, and have done to at break-neck speed. The edge they have over the established players is that they operate no physical stores, and that they use artificial intelligence based on the “consumer-to-manufacturer” (C2M) model to respond much faster to trends and customer needs.

The business model is referred to as “real-time fashion” or “on-demand fashion.” It means that customers can order goods anywhere in the world directly from manufacturers, which are predominantly located in China. The price level is even lower than that of the established “fast-fashion” chains.

It is estimated that the number of parcel shipments to Germany this year to date already adds up to around 30 million for Shein and to roughly twice that number for Temu. Both groups take advantage of the duty-free import of individual consignments (up to a value of EUR 150). Driven by their runaway growth, the companies have been investing in their logistics concepts in Europe. They already set up distribution facilities in Poland. The idea is to create a network of goods warehouses in Europe so as to be able to move inventory freely within the EU. This would also make it easier to comply with pertinent EU regulations. One risk that comes with the expansion is the contentment of customers who expect the product quality to meet the European standards they are accustomed to.

In the years ahead, TikTok could emerge as yet another potential demander. Its Chinese parent group, Bytedance, is currently investing heavily in the expansion of “TikTok Shop,” the platform’s integrated e-commerce solution. It enables users to order products directly as they are displayed on the app. Selling goods and services in this manner is also called “social commerce.” The concept has already proven quite successful in some parts of Asia. On a global scale, the market segment is projected to see tremendous growth in the years to come. In Europe, the concept is a rather recent arrival, and has mainly been applied by Shopify so far. Choosing the UK as its pilot market, Bytedance has now started to invest in Europe as well – and it may expand into other countries.

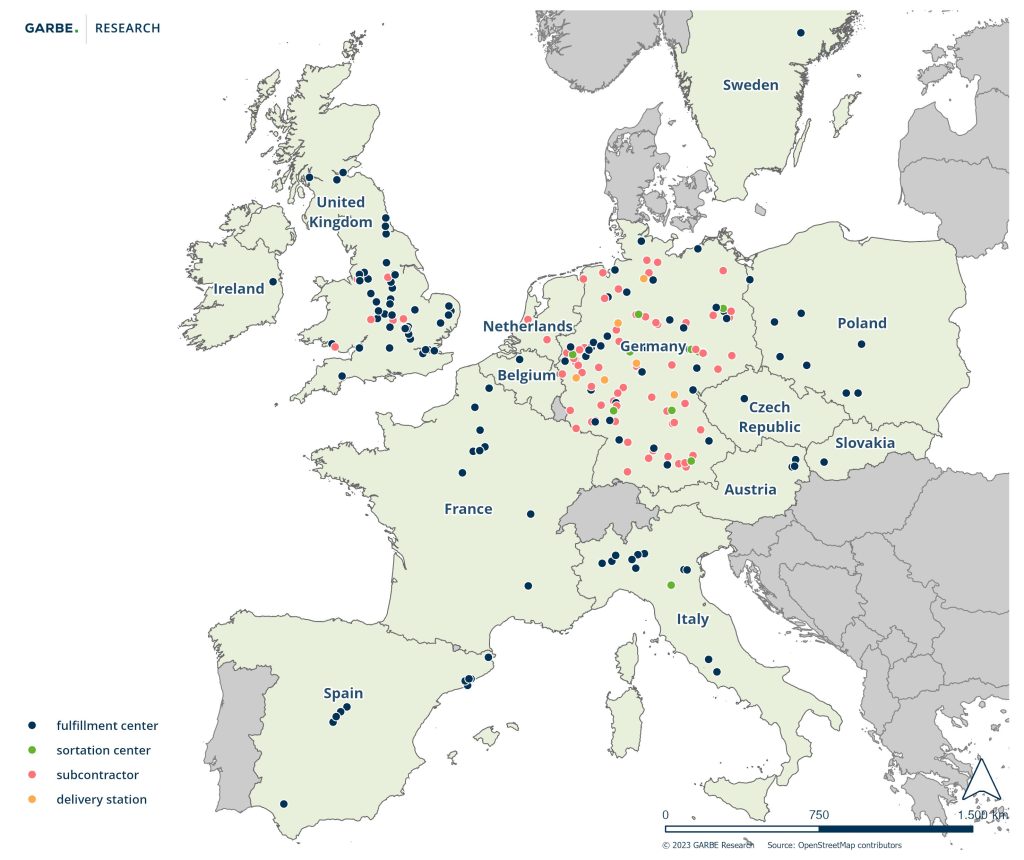

Amazon was one of the major demand-side players in online retailing in recent years. In Germany and elsewhere in Europe, the US group significantly enlarged its network of logistics, sorting and distribution centres. Within the scope of a survey, GARBE Research identified about 230 active Amazon sites in Europe, thereof 115 in Germany. Next in line came the UK with 57 sites, followed by Italy, France, Poland and Spain with ten to twelve assets in each. In 2022, Amazon increased the number of its sites in Germany by about one quarter.

Figure: Amazon locations in Europe

But even Amazon has felt the impact of declining online retail sales lately. Premises in 13 sites are to be sublet temporarily either whole or in parts in order to avoid overcapacities during the current market cycle. The advantage of subletting is that the floor area remains available on short notice whenever the need for extra space arises. It is therefore unlikely that Amazon will have a serious need for additional floor space to accommodate its classic online retailing business in the near term.

Rather, demand may be generated by the new “Supply Chain by Amazon” service that the company presented in September, offering third-party logistics (3PL) services. The new business model includes the options to supply the warehouses of other retail companies, to let warehouse space at Amazon facilities to others, and to provide goods fulfilment for other retail channels. This business line would not only make more efficient use of the company’s proprietary real estate but also move it closer to its goal to become “the world’s largest transport operator.” The US conglomerate would also enter into direct competition with delivery companies like UPS and FedEx. A successful implementation of this service offer would make it reasonable to predict further space requirements beyond Amazon’s existing sites.

Delivery concepts that registered enormous growth during the pandemic in particular are either consolidating or pulling out of the German market altogether. German consumer behaviour failed to shift permanently. In addition, the interest rate reversal made it harder to tap into venture capital.

With a share of barely 2%, groceries generally play a negligible role in the German online retail business still. Novice players on the market have an even harder time unless they enter into a collaborative venture with established market operators. A case in point would be the Dutch delivery service Picnic, who found a strong partner in German grocery giant EDEKA. By the end of 2023, nearly 60 distribution centres will be up and running.

The intention is to bring the e-grocery retailing share up to 8% by 2030 (c. EUR 22 billion). To keep others from muscling in on this market, Germany’s major players are investing in proprietary platforms or in collaborations with strategic partners. In addition to Picnic (EDEKA), there is Flink (of the REWE grocery chain) and REWE Digital. Both ALDI discount supermarket chains (Nord and Süd) have started operating a joint online shop for bulky goods specials. On top of that, ALDI Süd is currently trialling a delivery service in Mülheim, Duisburg and Oberhausen, three neighbouring cities in the Ruhr.

Given the firmly established structures of the German market, it is reasonable to assume for the longer term that online grocery retailing will be dominated by the four current top dogs. Players like Amazon have already withdrawn from the segment because setting up a proprietary new logistics network would have required prohibitively large investments in what is already a fiercely contested market. Future demand will primarily be generated by digitisation and the reorganisation of logistics processes as well as by the set-up of (small-scale) distribution centres.

The current geopolitical and economic parameters make it hard to venture reliably forecasts regarding the future demand for space in online retailing. The one thing safe to say is that the boom driven by the pandemic has come and gone, and that many companies have revised their growth strategies since.

At the same time, new players and business models are emerging that are either created from scratch (Shein, Picnic) or represent the spin-offs of physical retailers (Zara, ALDI). The associated space requirements are blurring the distinction between e-commerce and traditional in-store retailing.

Floor space take-up by online retailers will probably remain muted in the near term because of the current economic situation. Constantly shifting consumption patterns as well as the steadily growing market share of e-commerce are likely to ensure that online retailing will continue to be one of the major demand groups on the logistics real estate market.

We use cookies on our site. Some of them are essential, while others help us to improve this website and to show you personalised advertising. You can either accept all or only essential cookies. To find out more, read our privacy policy and cookie policy. If you are under 16 and wish to give consent to optional services, you must ask your legal guardians for permission. We use cookies and other technologies on our website. Some of them are essential, while others help us to improve this website and your experience. Personal data may be processed (e.g. IP addresses), for example for personalized ads and content or ad and content measurement. You can find more information about the use of your data in our privacy policy. You can revoke or adjust your selection at any time under Settings.

If you are under 16 and wish to give consent to optional services, you must ask your legal guardians for permission. We use cookies and other technologies on our website. Some of them are essential, while others help us to improve this website and your experience. Personal data may be processed (e.g. IP addresses), for example for personalized ads and content or ad and content measurement. You can find more information about the use of your data in our privacy policy. This is an overview of all cookies used on this website. You can either accept all categories at once or make a selection of cookies.